Lydia Schouten

Yes, There Will Be Singing In Dark Times

ROZENSTRAAT- a rose is a rose is a rose is proud to present Yes, There Will Be Singing In Dark Times by Lydia Schouten, in which she looks back on the development of her oeuvre after almost 50 years of artisthood. Early performances are brought to life in an experimental way, and a new video installation, produced by ROZENSTRAAT, is presented.

In the exhibition, Lydia Schouten focuses on the position of herself as both a woman and an artist. The videos and video-installations shown, present various personifications of the artist. She uses her body as a combative but also sensitive and contemplative subject, denouncing – sometimes with a wink – unequal gender relations and undermining social norms. Recognition, contact, loneliness, eroticism and travelling are guiding concepts in Yes, There Will Be Singing In Dark Times.

Partly prompted by her personal situation, Schouten’s early performances stemmed from an urge to wake people up, to make them realize what was wrong with the position of women and the expectations they had to meet. Moreover, much art was too far removed from her own frame of reference, and she wanted to change that.

In her most startling performance How does it feel to be a sex object (1978), Schouten is tied to elastic cords and hoisted only in a tight corset as she tries to smash ink-filled black balloons with a whip. Her head is rendered unrecognizable by a layer of bandages that were meant to protect her from the ink but could arguably also be seen as an indictment of the norm imposed on women of a perfect ‘make-up face’. In the performance, temper and fury alternate with exhaustion and despondency. But after her task is done, and all the balloons are broken, she briefly and almost triumphantly reveals her true face.

The performance I feel like boiled milk (1980) is more poetic and erotic in nature. Here, Schouten seems to act more inwardly. While rolling and spinning, through an apparently unrestrained choreography, she blurs a text applied with earth on wheat flour within the elliptical frame. The text alludes to her desire for contact and self-preservation. Is she trying to control her emotions and feelings, or is she giving them free rein instead?

In both performances, Schouten deploys her body ambiguously. She presents herself as both vulnerable and courageous. She provokes, seduces, and instils fear through her resolute actions. She has herself under control but also crosses (physical, mental, and social) boundaries – not in the least her own. In her performances, we seem to witness how she liberates herself from a position that is oppressive to her. At the same time, she demands more than a non-compromising response from her audience. ‘I wanted to touch people. To elicit a real reaction from them. They were my witnesses’.

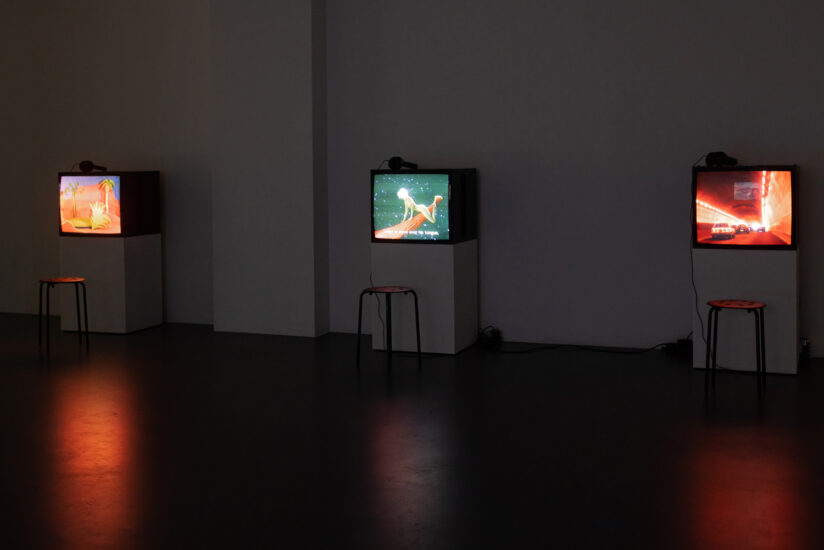

Decades later, Schouten’s performances hardly look dated and still retain their power and relevance. In ROZENSTRAAT, both works are shown in a new form, transforming from performance to video-installation, using recordings from the past. With this experimental, alternative performance, a new work was created.

The installation Please Touch (2024) also combines parts of existing artworks. It consists of a doll that persistently asks to be touched. In the here related video recording of the performance Smile (originally from 1979), we see how Schouten wraps a bandage around her head until her face is completely veiled, sheltered from the outside world. Smiling – something her mother advised her to do more than anything else to get a husband – is no longer possible. Schouten’s ironic solution is an awkward smile drawn with lipstick on top of the gauze. In doing so, the work seems to hint at the desire for contact on the one hand and the deployment (or not) of a clichéd female appearance on the other.

Until the early 1980s, Schouten’s performances remained close to herself, but in 1981, when she left for New York for the first time, she was determined to take a new artistic direction. ‘I work better when the contrast with the Netherlands is big. I need extremes,’ she told about her decision to leave. Yet performative art attracted her there too. In New York, she started making video art, which gave her greater freedom. She experimented unimpeded with the medium, which lent itself to different rhythm, sound, text, and surprising visual effects. Whereas her early performances were basically self-portraits, the focus in her video art shifted to (fictional) characters that did not have anything directly to do with Schouten personally.

Video art offered her the opportunity to play roles, as in The Lone Ranger Lost in the Jungle of Erotic Desire (1981) in which we see Schouten acting out erotic fantasies or in Romeo is Bleeding (1982) in which the artist acts as a seductive, tough but also lonely female adventurer. Again, Schouten avoids a one-size-fits-all approach. Later videos, such as Split Seconds of Magnificence(1984) and Echoes of Death/Forever Young (1986) take as their starting point the influence of the media on everyday life, and on women’s self-awareness and position in society. In these works, Schouten presents herself as a highly desirable femme fatale. But behind the dominant, self-conscious appearance also lurks insecurity and, again, loneliness. In the absurdist Songs of Innocence (1997), for which Schouten herself operated the camera, we once more see a powerful woman taking control. This time she is travelling alone in France. Looking for friendship, eroticism, or sex? Slightly more melancholic is From Lilac to Blue (1999), in which we follow the artist on a trip through America as she, based on spoken and written texts, reflects on her life.

Yes there will be singing in dark times (2024), Schouten’s most recent work, also has a reflective character. The video installation shows a swaying platform with two fictional figures and a representation of the artist herself, in a visual language that has been distinctive for Schouten since the early 1980s. As pirates, as Schouten likes to portray them, they travel through life, meet like-minded people, and grow, both personally and as an artist. In the accompanying video projection, we see the artist transcribing letters against the background of seascapes. The text was originally written by a woman who left Amsterdam for New Amsterdam in 1636. On her way to a new existence.